Understanding the Role and Importance of Community Banks

The recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank focused a bright light on community banks. Community Banks are the heart of the US Banking system, numbering about 4,500 with this number decreasing by about 100 banks each year.

According to the FDIC, these community banks “play a vital role in the functioning of the US financial system and broader economy, from lending to small business owners and farmers, to providing critical banking services in small towns and rural communities across the nation.”

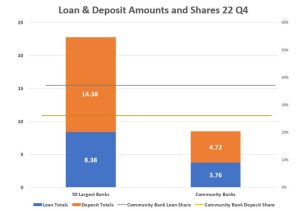

While flattering to the community bank segment, that definition of the role of community banks does not do these critical financial intermediaries justice. As of 12/31/22 community banks (banks other than the 50 largest banks in the US) –

- Held almost $5 Trillion in deposits

- Had almost $4 Trillion in loans on their books

Source: FDIC Call Reports

Additionally community banks:

- Provide about 60% of all small businesses loans

- Originate more than 80% of agricultural loans

- Have nearly 50,000 locations

- Employ nearly 700,000 people

Source: Independent Community Bankers of America

The Challenge Facing Community Banks

Immediately following the recent bank failures, deposits flowed out of community banks and into large money center banks seeking the apparent safety of “too big to fail” banks. While this surge has subsequently slowed community banks face significant challenges as interest rates rise, operating costs rise and the lines between mega banks and community banks seem more clearly drawn.

Here are two ideas for strengthening community banks

- Make deposit insurance available in amounts larger than $250,000 per account. Deposit insurance is the only type of insurance where “one size fits all”. There is no magic in the FDIC’s insurance of $250,000 per account. It is not tied to an inflation-based formula, it has simply been raised by congressional action to deal with then-current conditions.

Since 1934 the amount of maximum deposit insurance has been raised seven times. It was last raised from $100,000 to $250,000 in 2008 to bolster waning depositor confidence in the banking system following The Great Recession.

While $250,000 deposit insurance is sufficient for most consumers, many investors and businesses could be enticed to remain at community banks if additional account insurance was available.

Allow banks to decide how much insurance they need to provide to serve their depositors. Allow these banks to purchase additional deposit insurance.

Some banks may decide that the $250,000 base amount is sufficient for their depositors while other banks may, at their own expense, purchase additional deposit insurance. This also matches deposit insurance expense with the users of the insurance rather than apportioning premiums among all insured institutions as is now the FDIC’s practice.

- Encourage community banks to better compete with large banks by creating an incentive for community banks to create incentives for time deposits. Once upon a time, financial institutions provided demand deposit accounts (checking) and time deposits (savings accounts and CDs). An entire sector of financial institutions developed that provided only time deposits (Savings and Loans and Building Associations). People bought CDs or simply saved because the interest rates available were attractive and provided a risk free return.

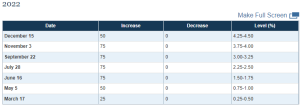

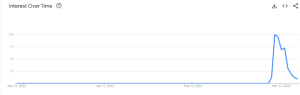

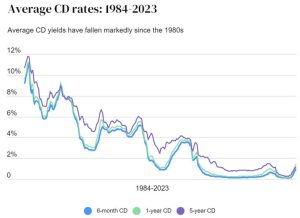

A quick Google search showed that today, investors can achieve 4% plus interest rates for relatively short-term CD but over time, the average CD rate has declined precipitously –

Source: Bankrate

Note that in 1984, investors were able to buy CDs with yields over 11%. It’s interesting to note that yield on the S&P 500 in 1984 was -5.9%. That’s negative 5.9%.

Let’s step back and look at that in real dollars. $1,000 invested in a CD earned about $110 while the same amount invested in the S&P 500 lost about $60. This makes a strong risk-free return look quite attractive.

By 2009, CD yields fell below 1% and yields virtually evaporated in late 2021 with banks paying .09% for a 6 month CD. Let’s put that in real dollars: $1,000 invested in a CD earned the investor 90 cents Yes, 90 cents. This seems like a disincentive to invest in a risk-free time deposit when the S&P 500 yielded about 13% that year. Clearly, investors were not motivated by the risk-free almost zero interest rates provided by bank time deposits. For over ten years, CD yields were not comparable with yields of other investments.

We suggest that the Treasury provide a credit facility available only to community banks that would allow the banks to offer a minimum 5% time deposit with at least a 100 basis point return. As interest rates float up, banks would not need to activate the facility as their return would be sufficient to encourage banks to offer attractive time deposit rates.

How could this work? Through a repurchase agreement. The US Treasury sells a treasury instrument to community banks with a remaining term approximately equal to the term of CDs sold. Contemporaneously, Treasury enters into a repurchase agreement with the community bank to repurchase the instrument in the future for an amount that would provide the bank with a 100-basis point return for the term of the CD.

This approach is consistent with the Treasury’s current moves to reduce the supply of money through Quantitative Tightening.

While 100 basis points would not provide a windfall return for the banks, it would provide a profit for community banks and a minimum 5% return might encourage investors to fly from at-risk investments to risk free investments at banks.

Offering competitive rate time deposit options to consumers might cure another national problem. It might help the 10% of Americans with no savings and the additional 39% of Americans who report that their savings balances are less than they were one year ago begin or return to saving.

Source: Bankrate

This solution might get America saving again.